NBA

Kendrick Lamar Gets Former Toronto Raptor DeMar DeRozan For ‘Not Like Us’ Music Video

Now, the Canadian singer-songwriter is adding ‘podcast host’ to his stacked resume. Dubbed

Our Way (naturally), his podcast is produced by iHeartMedia and showcases Anka alongside co-host and friend Skip Bronson talking shop with an eclectic array of guests including Michael Bublé, Clive Davis, Sebastian Maniscalco and Jason Bateman. (Bateman, who co-hosts the SmartLess: On the Road podcast alongside Sean Hayes and Will Arnett, also happens to be Anka’s son-in-law.) It’s the perfect medium considering Anka is bursting with stories: butting heads with Jerry Lee Lewis, hanging out with the Rat Pack in Las Vegas steam rooms, having Michael Jackson crash at his house. Did we mention the time Vladimir Putin sang to him?

Wondering where to start, let’s allow Anka to take the lead considering he recently added ‘interviewer’ to his skill set: “I brought The Beatles to the United States,” Anka declares. “We can start there.”

Let’s talk about you bringing The Beatles to America.

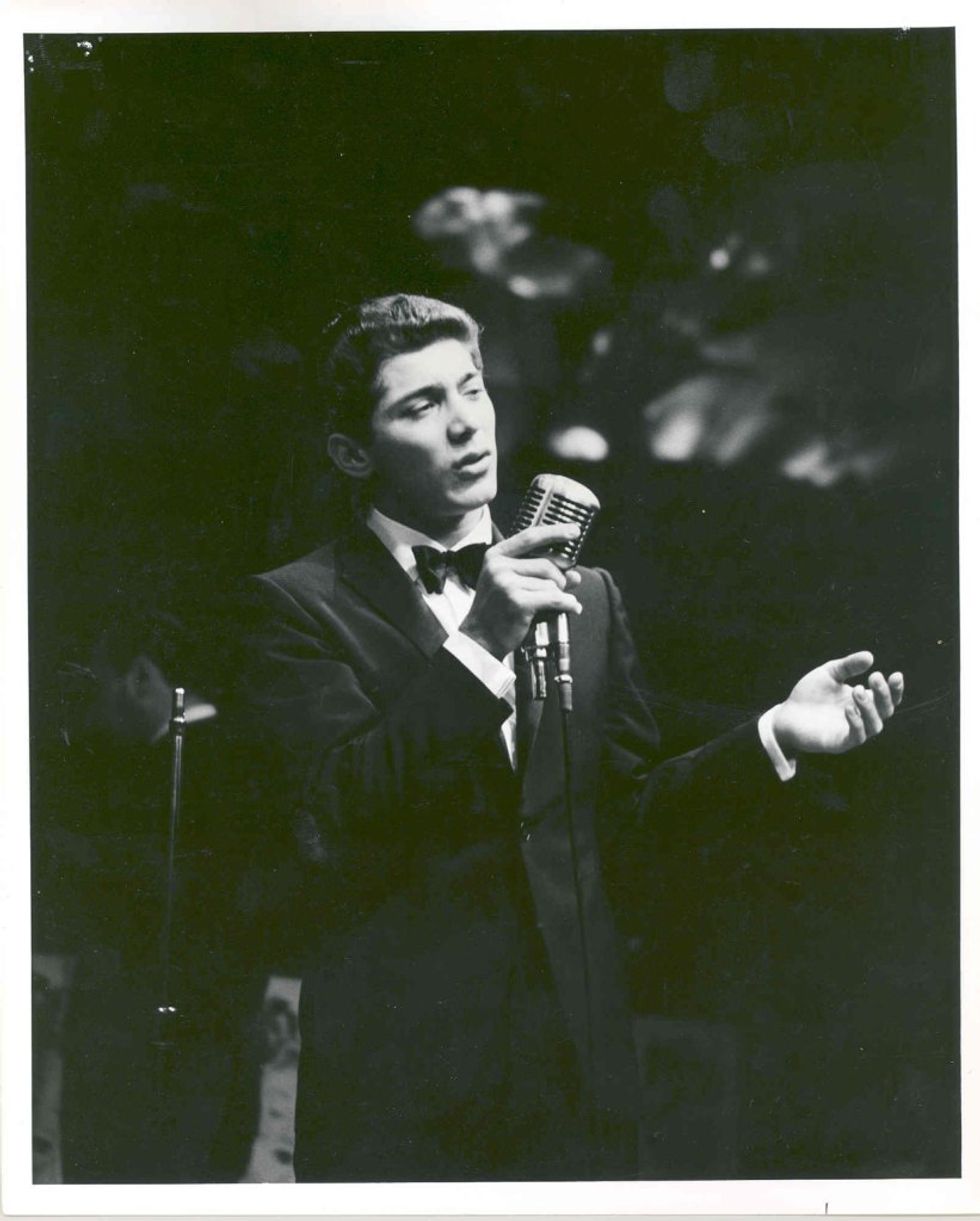

Well, I got my start before them. I got lucky in ‘55; I was the

luckiest teenager in the world and became an international creature traveling all over the world and wound up settling down with my wife in France, may she rest in peace. On one occasion in the early ‘60s, I went to Paris to see a friend of mine working at the Olympia Theater. In the course of it all, an announcer came on: “Ladies and gentleman, The Beatles.” I’m going, beetles? But these four guys came on. Being a musician, I was like, “Wow. What’s happening here?” So when I performed at the Olympia myself, they showed up to see me. We continued the relationship into London where we hung out socially. When I came back to New York where I was living part time, (I talked to) my agents at General Artists and I said to them, “There’s these guys! There’s something going on there.” I kept hounding them, and they went over and met with their manager Brian Epstein, and it evolved from that. They came over to Sullivan in ‘64 and all of the sudden music was a thing, like on Madison Avenue. When I was hopping around, it was a smaller industry.

Before The Beatles, you were a teen idol. Did you take full advantage of that?

It’s kind of like how it is today: same bullsh-t, more lights. But back then, we were under the thumb, if you will, of agents and managers because it was all new. I couldn’t leave my hotel because there’d be thousands of kids outside. I was living the dream but saying, “What’s going on here?” I was hiding away trying to deliver three albums a year.

Did you date any of the starlets of the era?

Starlets? Not really. I’m 15, 16 and 17. The only time I ever got serious was with Annette Funicello, a product of Disney who evolved to become America’s sweetheart. I wrote an album for her and we traveled together on tour. But much to the chagrin of the Disney people, I was trying to make the best of the situation. They had people around watching us and trying to curtail it. She wanted to get married and I didn’t, we were too young. Ultimately, she married my agent, Jack Gilardi.

Was there anybody you worked with or met who was most unlike their public persona?

Good question. Well, I knew everybody. We all traveled together and there weren’t a lot of venues. People like Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr. and Dean Martin, I saw their gentle sides; they were caring. Someone like Jerry Lee Lewis was wilder than I thought. I had to travel to Australia with him and he didn’t like me much. The most gentle, though, was Buddy Holly, who was my friend. We became very close and I knew everything going on in his life. We were going to start a company, and my manager booked him on that tour when he ultimately died [in a plane crash on Feb. 3, 1959, alongside Ritchie Valens and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson].

What was it like when you found out his plane had crashed? I know you even wrote a song for him, 1959’s “It Doesn’t Happen Anymore.”

It was devastating to all of us. We were very close. Unlike today, I’m not sure how close people are with each other when egos and narcissists emerge in the industry. But back then we were a bunch of close kids. Buddy was probably more talented than all of us. His music influenced us, too.

Who else influenced you at that time?

There was also The Everly Brothers, another major influence. But I’d go on tour with them and they wouldn’t even talk to each other; there was real hatred, fighting and carrying on, then they’d go on stage and that was it. So they were great guys, but they couldn’t be together or socialize and that was very sad to us. Chuck Berry was another wild man; we loved Chuck and his talent, and then we realized he was a real womanizer. It got to a point where if we had to take a bus from New York to a distant state, he was always wanted for something or other by the cops. So he had to be flown over two or three states where he was wanted, and then we’d have to pick him up. He ultimately went to jail at the end of that tour.

Tell me about your first time meeting Frank Sinatra.

For all of us, he was on our radar as someone we wanted to emulate: be like him, dress like him, play his same places. It was always Sinatra, Sinatra, Sinatra. He made it difficult for anybody to stand in front of a band after him. The first time I met him socially was at Trader Vic’s, the restaurant. I left my table and went over to introduce myself, intimidated to death. He was very kind and very nice to me. Once I started working in Vegas and hanging out in the steam room with him, we were friends. But I’m still very young. I’m still a kid in the steam room with all of these guys walking around nude trying to avoid eye contact.

What would go on in the steam room?

Unimaginable. I’ll leave it at that. Everybody’s walking around, having laughs, talking business. There were moments when certain times we’d have girls come in and meet us late at night. We were free back then — nobody was afraid of the press the way they are today. I wasn’t really asserting myself. But I certainly absorbed it, enjoyed it and went with the flow. I’ve seen a lot of experiences with him. When you went out with him, you brought your passport because you’d never know where you’d wind up. I saw a show with him in Philadelphia and he had his Learjet waiting. He said, “Come to New York tonight and stay with me.” When we got to New York, he said, “Let’s go to the boat” and we were going up and down to Connecticut. So the one night out turned into a week. It was monumental to me, because I had never spent so much quality time with him like that. We’d go out and there’d be cherry bombs being thrown around. It’d be a lot of frolicking around.

Another time we were in the Fontainebleau in Miami. There’d be holes in the wall, because the FBI was always trying to bug him which pissed him off. We got in there one night and it was late. He said, “Empty the terrace” and threw all these lawn chairs over the terrace on the beach. It was all kinds of fun stuff like that. There was nobody like him.

Is there a song you wrote that you wished Sinatra had recorded?

Well, one of the last ones he recorded but didn’t come out at the time, “Leave It All To Me.” It was actually only released a year ago or so. I kept pushing it and he finally recorded it, but he wasn’t well at that time and he left the studio early. They tabled it for a while and then put it out. So there you go!

Throughout your career you always championed artistic expression. I’m thinking of your album of rock covers, for example. But I wanted to ask you about two different moments, and very different artists. What did you think when Doja Cat sampled “Put Your Head On My Shoulder” for her song “Freak”?

Well, “Shoulder” started before Cat came along. It had a life before her and was very hot on TikTok. But I thought she was talented and knew her manager. They sent it to me for approval and I said, “Why not?” So I signed off on it and away she went and gave it that next life, if you will. I was in full accord. But we’re suffering badly from the music business today, there are no real great heroes happening with it. It’s all about (Daniel) Ek right now and streaming. The music industry is just not what it was anymore. So it’s getting very difficult to sell, so I said let Doja Cat go with it and see what happens. It’s very difficult for anybody to really be heard and seen today.

From one spectrum to another, Sid Vicious recorded a punk cover of your iconic song “My Way,” which famously featured at the end of the movie Goodfellas. How did that come about?

Sid called for a license and I said “no” originally to that, then said, “Why did I say that?” He was sincere. So I said, “Let me think about it.” I had to live with it for a while obviously. Once I computed everything and looked at it hard, I said, “Yeah, go.” And I approved it. Later (the director Martin) Scorsese called for a license to use it. I admire Marty greatly, he’s one of our greatest directors and I loved the cast.

Did you check in with Sinatra for that? After all, it’s by all accounts an insane cover of one of his signature songs.

No, an artist would have no say in that whatsoever unless you use his record. There were certain artists he would verbalize (not liking), but I’ll leave that alone. They were more in another vein. He didn’t like rock n’ roll music from the inception, we all know that. But in terms of “My Way,” I got no feedback on something that he disliked.

The legacy of “My Way’ is still going strong. In the past year alone, the song opened the broadcast of Super Bowl LVIII, was played at Alexei Navalny’s funeral, and is featured in the trailer for the new Brad Pitt and George Clooney movie Wolfs. What are your thoughts on this endurance?

Well, there’s actually a major documentary coming out about “My Way” which I think is going to Cannes next year. I can’t tell you what really jarred me aside from the Vicious record. I’ve been pleasantly surprised by many of the versions: the Gipsy Kings’ version is amazing, Brook Benton, Nina Simone’s version is amazing. I wrote when I was 25 after Sinatra told me was quitting. When I went to write it in New York, it was a spiritual moment; I don’t know where the hell it came from. What really jarred me in relation to the song, is when I started to hear what was happening in the Philippines where they take their karaoke

seriously: one person who sang “My Way” got killed, then another person got shot. I think it’s up to eight or nine people who got shot because they sang it wrong! I went to the Philippines just a few months ago and they said, “Yeah, it’s for real! If they don’t like the way you sing it, they shoot you.” And of course I’ve sung it all over the world, to presidents. To Putin.

Wait, you have to tell me what it was like singing to Vladimir Putin.

I had been to Russia a few times before, but singing to him (at a charity event in 2010) and knowing his station in life and his vibe was monumental and moving. He’s into the song, like a lot of others, for whatever reason. It was unlike anything I’ve ever done, and it paid off because I went to the Hermitage Museum with him after until three in the morning eating the greatest caviar I’ve ever had in my life.

What did you talk about?

He was gracious. He didn’t speak English that well, so there were interpreters and bodyguards. It was really about music. He loves the song “Blueberry Hill” by Fats Domino and played it on the piano.

You’re saying Putin played it on the piano?

Yeah, and he sang it. But we also talked about the art that was on the wall. But you have to be careful when you talk, especially with someone who’s not fluent with you. You want to keep civilized without him thinking, “Why am I being asked this?”

One more person I wanted to ask you about is Michael Jackson. He’s now this mythic figure, but what was Michael like one-on-one?

I go in with the Jackson family because they’d come to Caesars Palace to see me or Sinatra when he was much younger. But when he started to take off, I was with Sony Records when he was there. In the early ‘80s I was doing an album of duets and I got a call that he wanted to be part of the project. We already had people like Michael McDonald and Kenny Loggins, but I liked how Michael was evolving. He came out to my house in Carmel, California and stayed with us; that’s when I really got to know him. You know immediately this is a talented person. I was listening to the sounds and arrangements in his head and I’d be banging away at the piano, feeling it differently than anybody else I had worked with. He had that honest innocence. Michael was a sponge too, he wanted to know everything that I could teach him. We talked a lot of shop. We even had conversations about plastic surgery… We know where he went with that. I remember him being competitive with the Osmonds at the time. But I loved Michael; he had a sincerity, a love and a passion for show business and what he was doing.

We wrote three songs, including “This Is It” and “Love Never Felt So Good.” Years later, Drake showed up at my house to work on another track, “Don’t Matter To Me.” Working with him was different because he was all computer stuff. But the only negative part for me with Michael was when he took the tapes out of my studio, because

Thriller was taking off and he changed his mind about what we worked on. But I was already into it, spent my money and was getting ready to sweeten them. I ultimately got my tapes back. All of the other stuff with Michael is none of my business, it’s all unfortunate. The Michael I knew was gentle, complimentary and a friend. And that was it.

You went from records to the streaming era as host of the Our Way podcast. What’s it like navigating the show? Do you enjoy interviewing people?

I like it conceptually, and I was living vicariously through it with my son-in-law Jason Bateman who has the best one,

SmartLess. I was approached a few times after I did that one, and Howard Stern. I like to talk very openly and honestly, so timing is everything in my business and now I have talked to people like Clive Davis, Gayle King and Bill Burr, and sit there for an hour and a half and just talk. But what I also like is that I’m a listener, and I love it.

You were always the young guy working with these older artists. How do you feel now that it’s flipped?

Well, it’s great living both sides. It’s gratifying that I’m here still doing what I love, and still working and advising. Someone like Michael Bublé has been a dear friend and we talk constantly. Young people don’t understand how we’d go in the studio without any technology except a piece of tape, then rehearsed and rehearsed until we got it. Instead of now, “Oh, we’ll take a year to do this.” But giving wisdom and direction is very heartwarming. The greatest thing in life and my biggest thrill is when you give and see what it does for people. When I was a kid, even the guys I was hanging with like Sinatra or Dean Martin, nobody came from a sophisticated background. We all got lucky and found our groove and vibe. Now I wear the hat of the guys I witnessed; you become who you see. At my age right now, I still do that. And while I enjoy it, I also don’t look at life through a rearview mirror. If you stand still, they throw dirt on you.