World

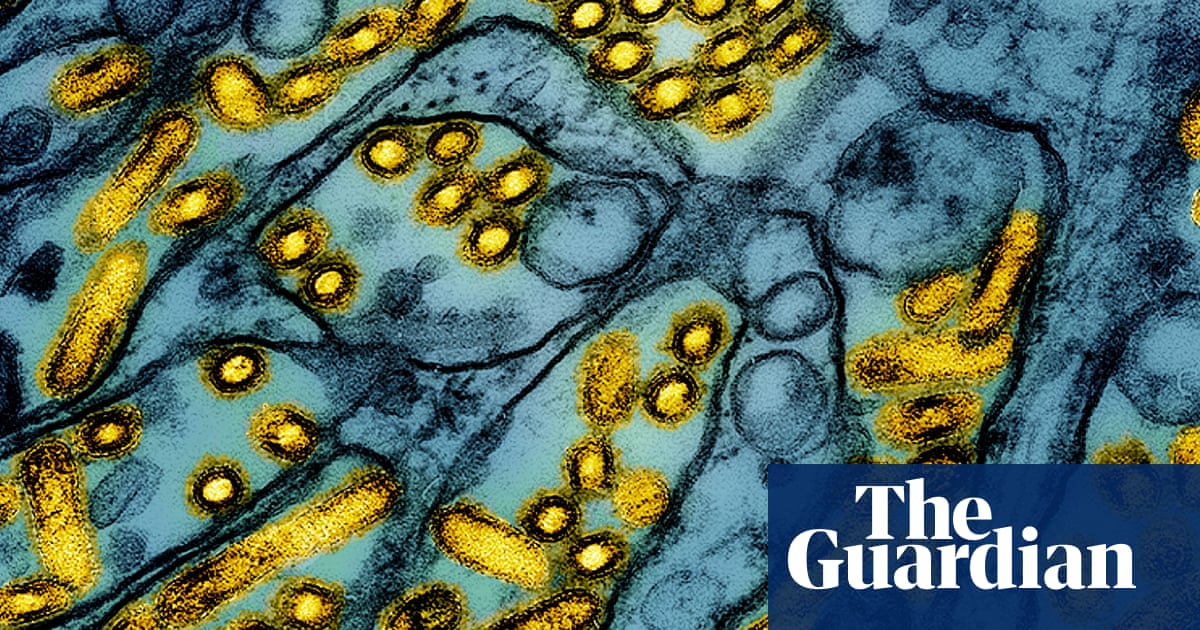

Bird flu in Canada may have mutated to become more transmissible to humans

The teenager hospitalized with bird flu in British Columbia, Canada, may have a variation of the virus that has a mutation making it more transmissible among people, early data shows – a warning of what the virus can do that is especially worrisome in countries such as the US where some H5N1 cases are not being detected.

The US “absolutely” is not testing and monitoring bird flu cases enough, which means scientists could miss mutated cases like these, said Richard Webby, a virologist at St Jude children’s research hospital’s department of infectious diseases.

“We need to be following this as closely as we can. Any advanced warning we can get that there’s more viruses making these types of changes, that’s going to give us the heads-up,” Webby continued.

The Canadian teen first developed symptoms on 2 November and was hospitalized at the British Columbia children’s hospital on 8 November. The child is still in critical condition with acute respiratory distress – a serious lung condition that can be fatal.

Preliminary sequencing of the H5N1 variant sickening the teenager showed a potential mutation on the genomic spot known to make people more susceptible to the virus.

That could indicate that H5N1 has the capability to become more like a human virus, rather than an avian virus, but it is also not clear yet whether this change is meaningful and more dangerous to people, experts said.

The virus may have mutated over the course of the teen’s illness; additional sequencing could reveal more about its evolution.

“Often it’s not just one thing that is going to confer that ability” to infect humans more effectively, said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan.

“It’s not quite clear what the real-world implications are going to be, but certainly all of these things are a warning sign,” Rasmussen said. “We really do need to pay attention to this, and we really do need to try to reduce more human infections as much as we possibly can.”

The particular variant of H5N1 circulating among birds in British Columbia and the north-western US appeared over the past few months, several years after bird flu was first found in North America, Webby said. The variant also sickened 11 workers in Washington state who were killing infected poultry, though those workers did not have the possible mutation detected in the teenager.

“It seems to be pretty active in terms of infecting animals, infecting people, so I think it’s one to keep an eye on,” Webby said. “It has some unique properties we just need to watch.”

There have been no additional cases detected among the Canadian teen’s contacts, including family, friends and healthcare workers. The teen’s case was detected through disease surveillance – the regular examination of positive flu cases – at the hospital, and no other cases in the area have been discovered through that system.

“We have strong influenza surveillance in BC and have had an increase in testing requests for H5 and all negative to date,” said Bonnie Henry, an epidemiologist, physician and the provincial health officer at the British Columbia ministry of health.

Canadian officials have been conducting blood tests among the teen’s contacts, and they expect results later this week. They are also awaiting the results of other tests done over the weekend.

Officials are “still hopeful on the exposure side to find how the young person was infected but nothing yet new to report”, Henry said.

after newsletter promotion

Though there have been outbreaks of H5N1 among poultry in British Columbia, the teen did not have exposure to them – but he or she did have contact with several pets, including dogs, cats and reptiles.

It is possible one of these animals encountered a dead bird or animal and passed the virus on to the teen, Rasmussen said, adding: “I don’t think that people realize how often we can come into contact with wild animals, including birds.”

Canadian officials have worked to detect cases like these quickly, Rasmussen said.

“There’s always more surveillance you could do. It is not, however, like the US, where they seem to be actively resisting testing animals and people,” Rasmussen said.

“It, to me, is absolutely stunning that they don’t test every animal on a farm after it’s been found to be infected,” she said. Farm owners and workers have been resistant to testing for social, financial and legal reasons, and workers have often been kept in the dark about outbreaks – putting them at greater risk of getting sick.

In Canada, experts hope the mutated virus will die out without being passed on to anyone else. “If there are any additional human cases, those will be isolated as well, and that means that this virus has hit a dead end, evolutionarily,” Rasmussen said,

But if the mutation happened once, it could happen again – a particular concern among less-well monitored populations, she said.

“If we have human cases that are undetected, that increases the risk that some of these viruses could be passed on, and by the time we do detect them it might have spread further,” Rasmussen said. “That’s why we do need to remain very vigilant about this.”

The possibility of a more-transmissible virus was a warning sign, Webby said. It “stresses the need that we’ve got to do something about this virus. We’ve got to get it under control.”