Tech

One year later, what filled the hole SVB left in Canadian tech lending?

Venture debt lending has slowed but ex-SVB talent has spread across Canada’s innovation banking practices.

When Aaron Bast describes the Canadian tech lending space without Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), he can’t help but reach for a local metaphor.

Bast, the Waterloo, Ont.-based general partner at Graphite Ventures, a venture capital firm focused on seed-stage startups, recalls the Waterloo Region’s “fear, shock and awe” after Research In Motion’s implosion in 2012.

“[People wondered], ‘Is it gonna cripple the community in Waterloo?’ But we were ready the best we could be, and the community got stronger as a result,” he said. “That could be said about how the Canadian banking community was able to absorb and step up and fill the gap left by SVB.”

One year after the collapse of SVB—which saw a bank run inspired by concerns about the bank’s liquidity lead to a swift shutdown by regulators and eventual sale to First Citizens Bank in the U.S.—venture capitalists and lenders BetaKit spoke with said the ecosystem is missing one of a small number of doors to knock on for debt funding.

Venture capitalists and lenders BetaKit spoke with said the ecosystem is missing one of a small number of doors to knock on for debt funding.

But the bank’s four-year run in Canada changed the tech lending landscape significantly, with its presence prodding the Big Five banks to start competing for startups’ business and giving smaller companies better access to bank pricing for debt. With those banks hoovering up former SVB Canada talent and customers in the past year, and National Bank of Canada acquiring its Canadian portfolio in August, the country’s major financial institutions are set to be more active tech lenders.

“All the players now have new DNA and a focus on the potential of tech companies to become strong depositors,” said Matt Roberts, co-founder and general partner of CMD Capital, a seed stage-focused VC firm. “I think you’ll see ex-SVB people in senior positions all over the innovation and financial industries for the next generation.”

Tony Barkett, head of technology and innovation banking at RBCx, said the tech lending market is “the most competitive I’ve ever seen” since he started working for SVB in 2010. He attributed the competition to a combination of a larger number of lenders and far fewer startups looking to raise capital, with macroeconomic conditions having pushed many to the sidelines.

Unlike traditional debt facilities for more mature companies, venture debt—a type of non-dilutive funding—is geared to early-stage companies that are often still cash flow negative and don’t have assets against which to lend. Structured as a term loan with a principal and interest payments, venture debt facilities are offered to venture-backed companies during equity rounds and providers tend to rely on the due diligence of VCs to assess the growth potential of borrowers. The debt, which is used as working capital to help companies get to their next raise, is paid back ahead of equity holders in the capital stack.

Big Bank battle

CIBC Innovation Banking—long a leader in the venture debt space since its acquisition of Wellington Financial in 2018—maintained its dominant position over the past year. The bank was the top venture debt provider by both deals and dollars in 2023, lending $113 million over 15 deals, according to the Canadian Venture Capital Association’s (CVCA) 2023 annual report. That included an undisclosed debt facility to Toronto wealth management platform d1g1t, and a $3.5-million CAD debt facility to Edmonton AI-based maintenance solutions provider Nanoprecise Sci. Corp.

Espresso Capital was the second-largest venture debt provider by number of deals, at $21 million over 13 deals, and Investissement Québec was third, with $93 million over seven deals.

Multiple VCs cited more recent entrant RBCx as being active in the past year and committed in the early-stage space. RBCx, which launched its venture debt product in 2021, hired four former SVB Canada employees in November last year and rolled out its early-stage banking platform around the same time.

“RBCx is a solid platform, they’re more strategic in the deals they do,” said Christian Lassonde, founder and managing partner of Impression Ventures. “They’re out there, active, and relevant.”

Bast said his portfolio companies have primarily dealt with CIBC, RBCx, SVB before its collapse, and Comerica, but he didn’t see other banks as active in the early-stage space. “Maybe they’re very, very strong way downstream at the pre-IPO stuff; I just don’t see them as much,” he said.

Two sources told BetaKit that after its August 2023 acquisition of SVB’s Canadian loan book National Bank has been unexpectedly quiet. The acquisition included $1 billion CAD in loan commitments to SVB’s Canadian customers, about $325 million of which were outstanding at the time of the deal.

“I’ve not seen National Bank be nearly as active as I thought they would be,” said one VC, who asked not to be named to speak freely about the differences between financial institutions. “I thought they’d buy that platform and try to activate it and maintain the leadership that SVB had. So far I haven’t really seen that.”

Roberts said the bank is doing deals and looking to establish itself, but is still working to build relationships outside of Québec. “National Bank was trying to get into this space and in Québec they have a large presence, but they did not have, for lack of a better term, an English-language equivalent.”

Michael Denham, vice-chairman of commercial banking and financial markets at National Bank, told BetaKit he was “not surprised” people hadn’t heard much from the bank, as its culture is to act rather than talk. “The VC community is well aware and highly supportive of what we’ve done,” he said. The people who need to know know, and they see what we’re doing. The fact that others don’t hear a lot of noise frankly doesn’t concern me.”

National Bank has hired a number of ex-SVB Canada employees since the acquisition, which Denham said has given the bank a stronger tech investment banking presence outside of Québec. He said the bank’s loan book has also given the bank more balance between Québec and English Canada clients.

Since August, the bank has been working with the clients it acquired from SVB’s portfolio to shift their banking services over to National, if they weren’t already clients, and work with them to improve their cash management position. It also extended “a number” of venture debt facilities to existing and new clients, he said. While the bank’s bread and butter was historically lending to later-stage companies, Denham said the acquisition included a number of early-stage startups and the bank has been learning.

“I’m pleased with what we’ve done since the acquisition. We attracted employees, got close to a lot of these clients and a lot have moved their banking and deposits to us,” he said.

Denham said the bank is “more comfortable” lending to cleantech and SaaS companies, and prefers B2B over B2C.

Pumping the brakes

The past year has seen a quieter lending market, but it has little to do with SVB’s absence.

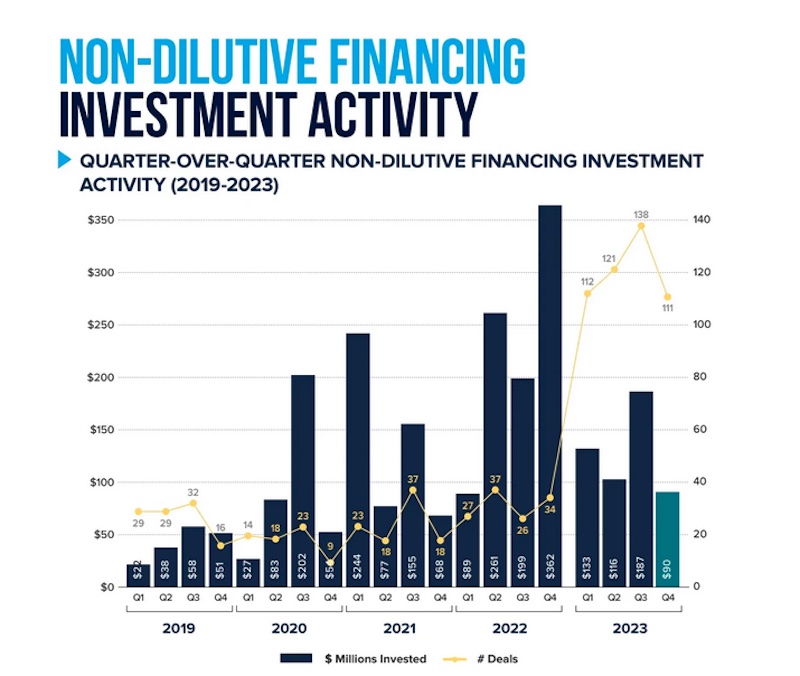

Venture debt deals slowed last year, representing just 10 percent of all non-dilutive financing in 2023, according to the CVCA report. SR&ED-backed financing represented the other 90 percent. It was a significant drop from 2022, when $664 million was disbursed over 124 deals.

Roberts said there’s “very little [classic] venture debt going on in the ecosystem right now,” as the velocity of equity rounds has decreased in the wake of higher interest rates. Last year saw a total of $6.9 billion invested over 660 deals, well down from $10.5 billion across 760 deals in 2022 and $15.7 billion over 847 deals in 2021, according to the CVCA report.

With time between raises stretching out, Denham said venture debt requirements have become “longer and thinner,” and many startups have worked on their cash management to lower their burn rate. “As a lender, you have to be comfortable with the extended timeframe, but the amount you’re needing to disperse to cover the cash requirements is a lot less,” he said.

Roberts noted that the banks’ credit risk strategies, given the impact of higher interest rates on consumers and businesses, could be part of why the lending market is slow now. Canadian banks licensed by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions to take deposits and issue loans must set aside funds to cover loans that could go sour, which is meant to protect depositors if borrowers default.

It’s something that made them historically careful about traditional venture debt lending (SVB—which only had a license to lend and didn’t have to hew to those same provisions—had more flexibility). As of their 2024 first-quarter results, released late February, the Big Five have set aside a combined $3.9 billion in loan loss provisions.

Barkett said there’s been “no discussion internally from a credit risk perspective on holding back on venture debt,” however. “What we look at is quality deals, really good companies to back, and if you do that over time the portfolio plays out. We’re trying to do that on the front end, but there’s been no discussion on not doing new term sheets because of any sort of portfolio risk.”

The “wild wild west”

For those companies that can raise capital, Barkett said they have their pick of lenders and should assess what additional services they can offer startups, rather than just the debt. “If you’re able to raise capital it’s a great time to be an entrepreneur, there are a number of partners on the debt side looking to help you out,” Barkett said.

Denham, who characterized the market as a flight to quality, was more moderate. Good-quality startups have options, he said, but wouldn’t agree that life is rosy. “I think two years ago there was a sense that every VC-backed company would succeed, and as a result, there was lots of venture debt. Now people are a bit more realistic, some companies do have the basis for success and some don’t.”

Mark McQueen, former president and executive managing director of CIBC Innovation Banking, agreed. Even with higher interest rates, the cost of debt is still competitive, and the taps haven’t turned off.

“I think every good company still has ready access to debt term sheets, whether that’s from banks or from funds, and that’s the same as two years ago,” he said, adding that the private debt market was “way larger” than just three to five years ago, and there were more venture debt funds in North America now than at any other point his 25-year career.

For most of the last three decades, he continued, the cost of equity funding sat at around 35 percent, and the cost of debt between seven and 18 percent—except for—the last few years when equity was extremely inexpensive and companies loaded up.

McQueen said his sense of venture debt pricing is consistent with where it was about a decade ago. “There were a lot of great companies created 10 years ago that raised debt, and if you can get money at six [percent] it’s better than at 12 [percent], but if the cost of equity’s 35 [percent], then obviously you’re a happy camper.”

Barkett described the debt market as the “wild wild west,” with some lenders looking to gain market share by offering larger debt rounds than early-stage companies could normally access: $5 or $6 million of debt financing for a startup raising a $10-million Series A, when a normally they would have been able to secure a $3-million debt facility.

While that kind of offer can be appealing, it risks those companies’ ability to raise the next round, as it loads the balance sheet with more debt than they may be able to handle. “That’s where I think the market’s gotten a little bit crazy, because the term sheets have gotten very, very aggressive and more debt is not necessarily a good thing…especially when equity rounds are few and far between,” he said.

He also said some lenders are choosing not to include warrants in term sheets. A warrant gives a debt provider the right to buy company stock in the future at an established price.

“I think warrants are an important part of venture debt. When you’re taking warrants as a lender that allows you to be patient and flexible because there’s upside,” he said. “If I don’t take any warrants there’s no incentive to help that company.”

Roberts saw the warrant-less deals differently: as lenders questioning whether there was any value in the equity options of a company, given how unclear valuations are currently, and thus looking to just benefit from higher interest rate payments